Flute Fingerings

Feb 26, 2015The Science and History Behind Flute Fingerings

One of the first things that a beginner flutist must learn is flute fingerings. While this can be confusing at first, for the most part these fingerings follow a pretty logical progression. You lift up fingers to play higher, and you put down fingers to play lower. Lots of times this involves lots of memorisation and

referring to a good fingering  chart. However, while most flutists work hard to learn how to finger notes, they don’t ever stop to consider why that particular combination of keys produces a certain tone. The answer to the question of why has both a scientific and a social component. On the one hand, as a physical object, the flute is bound by the laws of acoustics and physics, which control what is physically possible to do on the flute. On the other hand, nothing is possible on the flute without the minds of great instrument makers who develop systems of flute fingerings that are based on the demands and technology of a particular time. Below, you’ll find some basic introductory information about flute fingerings. We’ll cover the acoustic aspects of playing the flute, as well as look at some information about the 19th century flute maker whose fingering system has dominated the concert flute world ever since.

chart. However, while most flutists work hard to learn how to finger notes, they don’t ever stop to consider why that particular combination of keys produces a certain tone. The answer to the question of why has both a scientific and a social component. On the one hand, as a physical object, the flute is bound by the laws of acoustics and physics, which control what is physically possible to do on the flute. On the other hand, nothing is possible on the flute without the minds of great instrument makers who develop systems of flute fingerings that are based on the demands and technology of a particular time. Below, you’ll find some basic introductory information about flute fingerings. We’ll cover the acoustic aspects of playing the flute, as well as look at some information about the 19th century flute maker whose fingering system has dominated the concert flute world ever since.

The Acoustics of the Flute

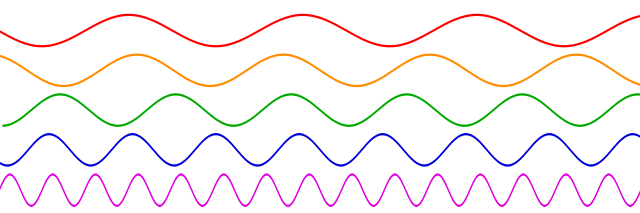

Before we get into the specific ways in which sound is produced on the flute, it’s important that you understand the concept of sound waves. When vibrations travel through the air the resulting sound waves oscillate between two points, which when graphed look very much like actual waves in the water. The value of the two points that the sound wave moves between and the speed at which it moves between these two points influences the pitch of that sound wave.

On the flute, these vibrations are caused by blowing a fast stream of air across the lip plate (sometimes called the embouchure plate). When the stream of air reaches the other side of the hole on the plate, it is diverted into two possible directions, due to it hitting the sharp edge of the hole. Some air continues to flow across the top of the lip plate, while other air is directed downward into the flute. However, this does not happen simultaneously. Instead, the air stream is quickly moving back and forth between the two, and this rapid alternation is what causes the sound producing vibrations of the instrument. Like the graphed sound waves, the air oscillates down the length of the flute. The rate at which this oscillation takes place is determined by which flute fingerings are being used by the musician. When fewer keys are pushed, the air vibrates at a higher frequency, which causes the pitch of the note to be higher. When more keys are pressed, the note will vibrate at a lower frequency and will consequently sound lower in pitch. While this is a good introduction to the acoustics of the flute, it only touches the most basic points. Things get considerably more complicated when it comes to producing different octaves on the flute and when you reach the uppermost register of the instrument. However, don’t let this deter you. The physics of music are an important and fascinating aspect of the music making experience.

On the flute, these vibrations are caused by blowing a fast stream of air across the lip plate (sometimes called the embouchure plate). When the stream of air reaches the other side of the hole on the plate, it is diverted into two possible directions, due to it hitting the sharp edge of the hole. Some air continues to flow across the top of the lip plate, while other air is directed downward into the flute. However, this does not happen simultaneously. Instead, the air stream is quickly moving back and forth between the two, and this rapid alternation is what causes the sound producing vibrations of the instrument. Like the graphed sound waves, the air oscillates down the length of the flute. The rate at which this oscillation takes place is determined by which flute fingerings are being used by the musician. When fewer keys are pushed, the air vibrates at a higher frequency, which causes the pitch of the note to be higher. When more keys are pressed, the note will vibrate at a lower frequency and will consequently sound lower in pitch. While this is a good introduction to the acoustics of the flute, it only touches the most basic points. Things get considerably more complicated when it comes to producing different octaves on the flute and when you reach the uppermost register of the instrument. However, don’t let this deter you. The physics of music are an important and fascinating aspect of the music making experience.

Theobald Boehm - The Man Who Changed Flute Fingerings Forever

Before the Romantic era of Western classical music (roughly 1800-1900), instrument manufacturing was not an organised affair. Instruments were constructed in wildly different ways depending on where they were being built and who was building them. However, in the 1800s, thanks largely in part to the industrial revolution, instrument makers now had the technology to standardise the manufacturing process. It was during this time that Theobald Boehm was looking to optimize flute fingerings systems and invented what is now commonly known as the Boehm flute. Boehm’s new flute model spread quickly in popularity and is still most commonly used by flutists worldwide today (although several changes have been made to his original).

Before Boehm, the tone holes of the flute were placed based on how far the human hand could comfortably reach on the instrument. However, this system was not acoustically ideal for pitch accuracy. To work around this, Boehm developed a quite complex system of keys that could operate tone holes located on other areas of the flute. This meant that players could use flute fingerings that were comfortable but still promoted a good, rich sound. Similarly, Boehm discovered that the flute had its best sound when the tone holes were too big for a player’s fingers to cover. So, to work around this, Boehm developed finger plates that could adequately cover the holes when depressed by the musician’s fingers.

Recent Flute Innovations

While the Boehm flute is still arguably the most popular model of flute in the world, instrument makers are still finding new ways to make improvements to both the tone of the instrument and the ease of playing.

For example, Jim Schmidt, an instrument maker from California, has developed what he calls a “linear chromatic flute.” Unlike the Boehm flute, which is based on the C major scale, Schmidt’s flute is based on the chromatic scale, which means that the instrument’s pitches move up a half step for every finger you raise. He argues that this system of flute fingerings is superior to the Boehm when it comes to executing fast, technical passages in keys with lots of sharps or flats and that the instrument’s fingerings are much easier to memorize since they follow such an intuitive progression.